Adivasis assert that Pithora is meant for the gods, not for commercial products.

While dedicated to preserving the form’s existence, practitioners actively oppose its application on clothing, bags, and other commercial goods.

In 2019, the JD Institute of Fashion Technology in Bengaluru hosted a fashion show featuring clothing adorned with motifs from Pithora, a traditional painting form practiced by the Rathwa, Bhil, Bhilala, and Nayaka Adivasis in the Chhota Udepur region of Gujarat, among other locations. The student curators, as mentioned on the institute’s website, expressed their intention to “enable the revival of the Pithora art form, to provide recognition and employment opportunities for the tribes.”

However, around three years later, when some members of these communities discovered photos of the show online, they were profoundly distressed, perceiving it as the commercialization of a sacred and ritualistic form. According to Sejal Rathwa, a journalist and coordinator of cultural documentation at the Adivasi Academy in Tejpur, Chhota Udepur, members of the Rathwa community view Pithora not only as art but as a sacred ritual commemorating their ancestors and gods.

In August 2022, members of the Rathwa community, through the Adivasi Academy, sent an email to the JD Institute, demanding the removal of photos from the show on the institute’s social media pages and website. They also urged the student designers to display greater cultural sensitivity regarding the sacredness of Pithora.

Despite repeated attempts to contact the professors and students responsible for the event, community members were unsuccessful. Sejal Rathwa was informed during a call to the institute that the students in question had already graduated by the time the email was received, and the institute lacked the authority to compel a response.

“People take these photos of Pithora from Google, and unthinkingly use it on clothes and other things,” expressed Paresh Rathwa, one of the well-known lakharas, or practitioners, of the Pithora form.

He remarked, “This is their ignorance. If they asked us to teach them Pithora, we would definitely do it. But we would also explain what the form means to us.” He reasoned that this additional understanding would likely deter people from disrespecting the sacred form.

This incident wasn’t the sole controversy surrounding Pithora in recent years. In 2022, members of the Rathwa community in Vadodara protested against a Pithora painting on a wall near the railway station, deeming it inappropriate for a place with heavy foot traffic. Following the protests, the Pithora mural was removed. Paresh Rathwa himself faced criticism in September of the same year after showcasing Pithora at an exhibition alongside the G20 summit in Delhi. In a social media post, he clarified that his goal was to raise awareness about the form, not to sell his work.

The matter is delicate. Like Warli, Gond, and Saura, Pithora is a well-known Adivasi art form. While artists of other forms have sold their works in response to government initiatives to promote and commercialize such forms, members of the Rathwa community remain steadfast that Pithora should not be commercialized through everyday products. Despite some artists from the community using Pithora for commercial purposes, they too maintain that it should not be replicated on clothing, bags, and similar items.

Sejal emphasized the difference in perspective between community members and outsiders, stating, “The sensitivity with which a community member who is an insider, and an outsider look at Pithora is not the same. It is important that the place and values that produce the art are also publicized with it.” This viewpoint is central to a complex negotiation within the community, aiming to ensure the survival and prosperity of the form while preserving its core values. In this process, the community strives to shield Pithora from various perceived threats, ranging from market forces to the risk of cultural erasure by non-Adivasis.

On the evening of October 15, I traveled from the dusty town of Chhota Udepur to the Adivasi Academy in Tejpur, surrounded by lush vegetation. As we approached, Koraj hill jutted above the horizon on an otherwise flat landscape.

Villagers advised against visiting the hill in the evening due to the presence of leopards. The next morning, just after dawn, I ventured to Koraj from the academy. The trail wound through fields of corn, pulses, and turmeric. As the morning sun painted the sky a cotton-candy pink, I spotted a peacock in the distance and noticed leopard paw prints on wet soil. Upon reaching the hill’s summit, I was treated to a panoramic view of the region. “Many Adivasi groups in Gujarat and neighboring Madhya Pradesh trace the story of their origins to this hill, suggesting that they may have been its early inhabitants,” wrote Alice Tilche, an anthropologist who studied Pithora and the Rathwa community, in her book Adivasi Art and Activism.

In 1994, archaeologists dated rock paintings inside a cave on Koraj hill to 12,000 years ago. These paintings depict human figures holding swords and riding horses, a motif central to the Pithora form. “We believe the rudimentary figures in the cave, made by our ancestors, must be the beginning of what has evolved to become Pithora today,” said Paresh Rathwa.

In the lore of Chhota Udepur Adivasis, Baba Pithora is the supreme deity, viewed as a king and an ancestor of the community. According to legend, to attain his kingship, Pithora, raised by a foster mother, set out to find his biological parents and claim his inheritance. After completing this quest, he was married and crowned king. Tilche, using an alternative spelling for the deity’s name, wrote, “The story of Pithoro growing up to become king despite all odds represents the possibility of success while bringing auspiciousness to the house.” Sejal Rathwa noted that Pithora’s stories were not documented in any texts. “In villages where the ritual occurs, there are songs that last the whole night,” she said. “These stories are mentioned in those songs. That’s where I found these narratives.”

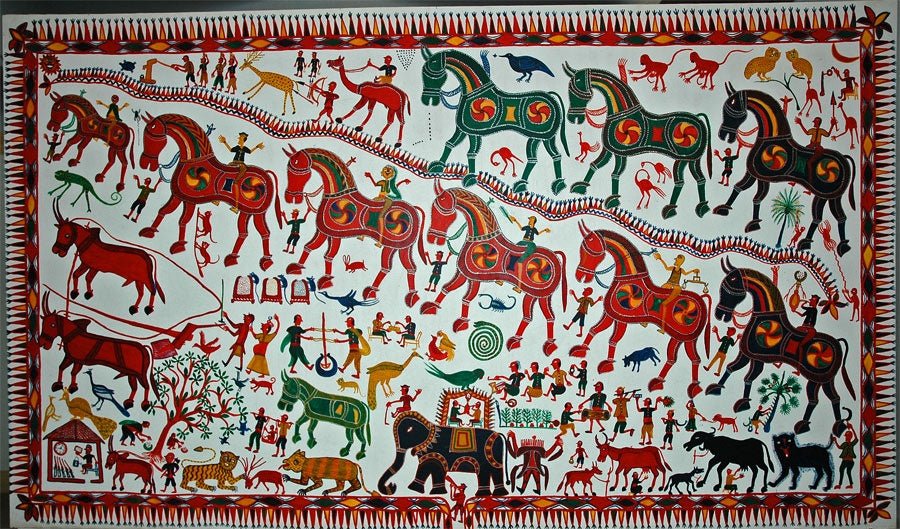

Adivasis of Chhota Udepur do not consider Pithora a mere art form but a sacred script, traditionally referring to it as written rather than painted, although in common use, it is also termed painting. “For us, it’s a script, but in front of the world, we’ll call it painting,” said Paresh. “Because they don’t know what it is. How many people can we explain this to? Others will always see it as art.”

Tilche emphasized in her book that “the painting is not a representation of the sacred but is in itself a sacred entity.” GN Devy, founder of the Adivasi Academy, mentioned in an article for The Hindu that “the making of Pithoro is the highest form of religion.” Paresh explained that the community prays to deities and nature through the form.

Currently, only five to seven families continue to practice Pithora, with members of two to three families actively participating in exhibitions. Traditionally, adult men become lakharas, learning Pithora from their fathers. Paresh, not born into a family of lakharas, developed an interest in Pithora and started practicing it at the age of 25 while working as a painter and designer. He fully dedicated himself to Pithora at 27, encouraged by the curator of the Tribal Museum in Ahmedabad.

Pithora, celebrating nature and the universe, incorporates motifs inspired by flora and fauna such as corn, mahua, toddy palm trees, deer, snakes, and leopards. The form, traditionally using natural ingredients for colors, is now often created using market-bought paint, with some lakharas incorporating new elements like Kutchi mirrors and silver paint.

The practice of Pithora involves a ritualistic vow by Adivasi families facing specific troubles, marking the occasion with celebrations and inviting lakharas to create Pithora on the main wall of their homes. Sejal highlighted that the associated beliefs are fluid, and the impact of Pithora on the family’s fortune varies.

In the early 2000s, Pithora faced extinction as religious sects entered society, diverting people’s attention. The entry of Hindu religious sects fragmented Adivasis, leading to a decline in the practice. Chhota Udepur, historically influenced by reformist movements promoting Brahminical reform, witnessed a slow erasure of tribal heritage.

Despite these challenges, efforts to revive Pithora succeeded through the 2010s, with increased awareness and the ritual becoming a way for families to assert their Adivasi identity for procuring Scheduled Tribe certificates. In 2021, Paresh Rathwa received the Padma Shri for his contribution to Pithora, leading to renewed interest and the training of new lakharas.

While practitioners are willing to teach Pithora, they resist its commercialization on everyday items. The community has declined requests to paint Pithora on clothing and similar objects. Practitioners balance traditional practices with innovation, occasionally depicting gods in modern attire or incorporating new elements in response to societal changes.

Despite their efforts, practitioners express concerns about official apathy, citing misrepresentation and erosion of Adivasi culture. A government catalog referring to Pithora as “Rathwa” painting exemplifies this challenge. The community remains vigilant, striving to preserve Pithora while navigating the complexities of tradition, modernity, and external influences.